12/01/2023 - 19/02/2023

Sala Dogana (Palazzo Ducale) Piazza Giacomo Matteotti 9, Genoa.

Curated by MIXTA (Silvia Mazzella, Arianna Maestrale) With Marco Augusto Basso.

Da Dogana a Ponte dei Mille is the winner of the call for a multidisciplinary project launched by the municipality of Genoa "Sala Dogana. Young ideas in transit" as a centre of experimentation of young art under 35; conceived by the curatorial collective Mixta and realized in collaboration with Palazzo Ducale, the Municipality of Genoa, the University of Genoa, the Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti and Villa Croce Museo d'Arte Contemporaneag and sponsored by Regione Liguria.

The composite and multidisciplinary project intends to stimulate the public's reflection on the multiple narratives of the city of Genoa: Da Dogana a Ponte dei Mille, in fact, plumbs the usual city's cruise tours, in the significant segment that goes from Ponte dei Mille to Piazza de Ferrari, and unfolds from an interactive exhibition, Janua, the work of two young emerging talents: Marco-Augusto Basso (born in Genoa in 1995) and Camilla Gurgone (born in Lucca in 1997).

The entire curatorial programme does not only present the Janua exhibition, but also offers the public a number of opportunities for talks and workshops in collaboration with wall:out magazine and the University of Genoa to explore in a participatory and active way the theme of "impossible archives" in history and artistic practice, but also the theme of "movements in the city" and the different practices of knowledge of the territory. The public meetings and the theme of the exhibition are intrinsically linked and aimed at researching new forms of interaction through the use of artist audio-guides, situationalist drift workshops and inclusive museum education projects.

The Janua exhibition

The artists Gurgone and Basso present according to their own artist flair a multimedia project realized as a duo especially for the spaces of Sala Dogana. The interventions of the two artists mix the field of physical reality with that of virtuality, both in the research phase and in the production phase, with the main aim of showing alternative representations of the city of Genoa, and consequently questioning the classical methods of museum archiving and narration.

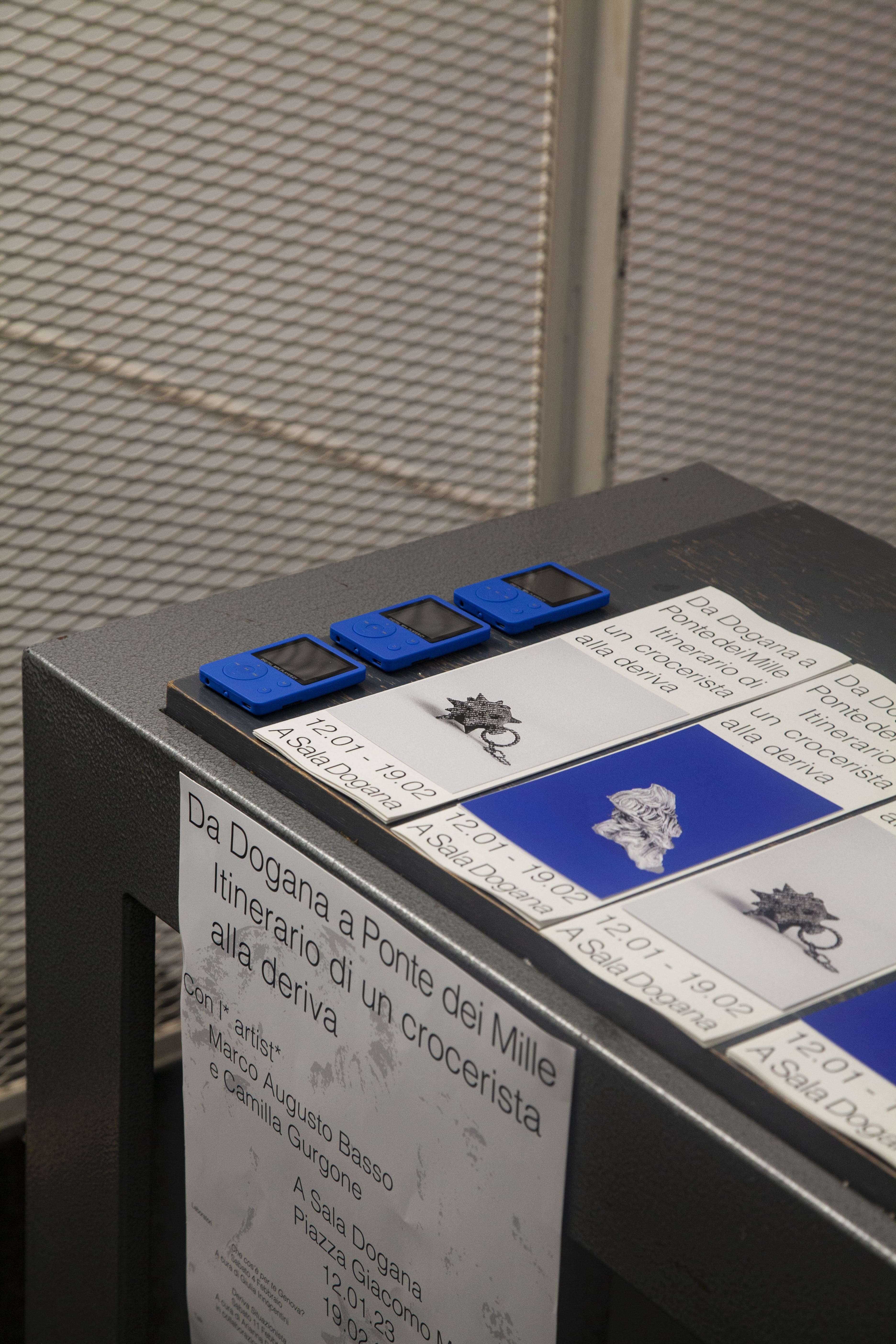

The exhibition in fact creates a meta-narrative through the concepts of historical fake and documentary fake. In this sense, the exhibition layout halfway between museum archive and wunderkammer aesthetics will be combined with real artist's audio-guides handed out at the entrance which the public will be able to listen to.

From the critical text: "Amidst unimaginable images and objects of ambiguous workmanship presented as objects and memorabilia “the sound of the guide seems to unravel the tangle of an obscure past that the city of Genoa has concealed over the years and to which we now finally have access. What emerges, therefore, is a warp of ambiguous and unknown stories that betray the obscene and the unspeakable that has never so far leaked from the city's history."

intallation view of the exhibition featuring the works of Marco Augusto Basso.

Route with audio guides created by Camilla Gurgone.

Audioguide text #1 - Introduction

Dear cruise-passengers, I am Camilla Gurgone and I welcome you to the beginning of our journey. Janua is an interweaving of stories and fragments of lives, brought together in this exhibition not only to immerse you in other points of view but with the intention of leaving you strongly questioning the idea you initially had of this city.

Even today, Genoa is still made up of hidden narratives, stratifications of a past that struggles to emerge. We will examine three places that are fundamental to the history of this city, from Palazzo Ducale to the Maritime Station at Ponte dei Mille, to Palazzo Caccialor, which belonged to one of the Rolli families. We will look at artefacts, objects and works of art shrouded in unknowns, including archaeology, love stories and a few little secrets.

Audioguide text #2 - The Doge's Palace: finds resurfaced from history

We all recognise Palazzo Ducale (The Doge's Palace) as one of Genoa's landmarks and are accustomed to frequenting parts of its halls during art exhibitions, festivals and other educational activities promoted by the municipality, but only a few citizens are aware of the multiple roles and aspects the palace has taken on over the years.

The many evolutions of the Doge's residence are clearly visible in the architectural structure of the entire complex made up of different stylistic components, which were progressively added as a result of the palace's numerous restorations. In the 1980s and 1990s, during one of the restoration excavations, researchers from the ISCUM cultural institute were commissioned to conduct a search for archaeological finds. In the east corridor of the Ammunition Hall, various historical objects and evidence of the palace's use from prehistory to the Middle Ages emerged.

Some of these sherds, however, present inexplicable elements and features that cannot be traced back to any historical period; plot holes that are still the subject of study and interest. Some shards of ancient ceramics found, for instance, present engravings and colours that are ambiguous for the Ligurian tradition: although the mixture and the pottery are of local origin, it has been confirmed that the subjects and pigments used refer to glazed and glazed ceramics of Islamic production, such as the specimen of graffito ceramics with the iridescent cross, formed by four columns in Moorish style, or the use of Pitzéco blue, a pigment that cannot be found and is only produced in the territories of Bosnia.

Among other finds, two objects seem to have undergone a mummification and crystallisation process never seen before. After careful analysis, researchers have linked this phenomenon to study items belonging to Constantino Grimalderi, one of the healing physicians who lived in the palace during the 17th century. Grimalderi, being forced to live confined to the palace like the Doge, used to carry out alchemy experiments, alternating between the use of stones and organic elements, partly taken from the corpses of the poorer classes. In fact, a brass medical vessel and some precious minerals were found near these findings, plausibly found by Grimalderi among the stalls of the general markets that at the time flanked the palace curtain on the south front. This market was known to sell and exchange exotic products, believed by the inhabitants to carry strong spiritual power.

Audioguide text #3 - Doge's Palace: the prison

One of the unusual roles taken on by the Doge's Palace was certainly that of a prison: the cells were developed on the upper floors, also involving a large part of the tower. The historical period in which the prison remained active is not well defined, but what we do know is that the cells housed prisoners even during the world wars. Among the tower inmates who served short sentences here were historical figures such as Nino Bixio and Garibaldi, but also countless artists, such as Domenico Fiasella and Niccolò Paganini. The prison gave the latter the privilege of passing the time by producing works of art, mostly consisting of sculptures made from recycled materials and frescoes painted on the walls of their cells. The subjects depicted by the artists, however, were the result of hallucinations and psychotic consequences, caused by the constant torture they endured during their imprisonment.

In what was once the torture room, some of the instruments used for the inmates' suffering are still preserved, now on display at Janua: one can see what remains of a spiked mace used to inflict physical beatings or the aforementioned 'practice of the mask-maker' in which prisoners were poured a layer of boiling wax over their faces to obtain a cast, later used by theatre tailors as a model for the creation of stage masks. Also on display is what remains of the skin of a snake, a specimen of Ipnalis, whose venom was used in the medieval period to cause hypnotic sleep or slow death.

Testifying to the delirium caused by torture are the works of the Neapolitan artist Carlo Borracci, who fled to Genoa after a series of crimes. A brawler, swordsman, sex maniac and sodomite, he was later convicted and imprisoned in the Doge's Palace for heresy, after drunkenly shouting blasphemous phrases. The frescoes, painted in his cell between 1640 and 1645 and now reproduced on canvas, depict a self-portrait and a recurring dream that Borracci recounted during his delusions: the scene of his own screaming wife while around her dozens of wild hares destroyed their dwelling, until the beasts themselves ended up as companions to live with and feed on.

Audioguide text #4 - The original Great Council Chamber

Inside one of the storerooms of the Doge's Palace, was found an archive of marble and plaster sculptural remains that originally decorated the Great Council Chamber. The hall we see today was reconstructed by architect Simone Cantoni following to the Jacobin popular uprising of 1797, which suppressed the symbols of aristocratic power and marked the end of the aristocratic Republic. The throne was destroyed, along with the statues of Illustrious Men that were positioned in the eight side niches and the statues of the Dorias on the entrance steps to the square.

Among the preserved rubble is a fragment of a bronze head, the work of Donato, a 16th-century Florentine sculptor who was commissioned by a wealthy patron from Genoa. According to what Giorgio Vasari writes in 'Le Vite', in the small paragraph dedicated to Donato's life, following a dispute between the two, the artist split the sculpture completely apart. We do not know why this fragment was archived with the others as it lacks the identification card.

Audioguide text #5 - Ponte dei Mille: a stream of stories

Now, let us shift the focus of our research to another landmark for this city: the Maritime Station and the influence that the Ponte dei Mille had on the migratory and transoceanic flow since the Genoese Maritime Republic. In the 19th century, population growth and the economic crisis gave impetus to the migratory phenomenon, which found in Genoa the best equipped port of departure for flows from all over northern Italy. At the same time, the elitist phenomenon of overseas leisure travel was gaining strength.

Thus, in 1914, it was decided to build a Maritime Station to meet the new needs. The building expressed a majestic monumentality, welcoming travellers into imposing halls decorated with large windows, coloured skylights and paintings portraying the cosmopolitan and elitist atmosphere of the great cruise ships of the time. For years, these salons accommodated the passengers of the most famous and largest ocean liners in the history of Italian shipping, which were engaged in scheduled connections with the Americas. Many personalities from the worlds of politics, culture and entertainment passed through the salons.

Some of the paintings on display in this exhibition were located in the former First Class Customs Hall on the west side of the complex. They were created between 1916 and 1920 by the Ligurian painter Vittorio Nattino, specifically for the setting up of the hall. It is peculiar how Nattino wanted to create images that would go beyond the depiction of an elitist class inclined to see only positive and boasting images and social prosperity around them. Muted and relaxing seascapes give way to storms ridden by fiery sailing ships, thunderbolts on the water, burning ships, war fields and riots. The artist, however, did not want to intimidate or frighten the passengers about to embark, quite the contrary: during the inauguration of the building, he declared that the images acted as a 'superstitious rite' and as a wish for peaceful navigation, also justifying how the painted images were the result of an imagination far removed from reality and emphasised.

Audioguide text #6 - Ponte dei Mille: objects seized from tourists.

Often, when tourists on transoceanic voyages boarded the ship for their return journey, it happened that they would take with them a souvenir of the city to lead to their loved ones. In this section, some small objects can be seen that can tell the story of those who crossed the Ponte dei Mille to embark or of the ships themselves moored at the station.A small Venus of Willendorf, reproduced in tin, was forgotten by a passenger in 1951, in one of the cabins of the liner 'Giulio Cesare', on the Genoa-Buenos Aires route.

These small metal objects with the function of talismans and good luck charms were mostly sold in small bazaars that temporarily invaded some of the city's squares. It is plausible that the passenger had bought the Venus as a wish for prosperity towards himself or towards someone who was waiting for him on arrival. In the 1950s, in fact, there was a drastic demographic decline in Argentina due to various factors, firstly with the worsening economic situation, then increased by the spread of Poliomyelitis, an extremely contagious infectious disease that can damage the nerves of the nervous system and induce partial or total paralysis of the body's muscles.

Did you know that most of Genoa's public statues have severed fingers? The phenomenon is due to a vandalistic tendency that developed in the 1970s and 1980s among tourists who visited the historical centre. Unlike other Italian cities, Genoa did not have a real monument to reproduce in a souvenir, leading visitors to the inclination to cut off their fingers in statues such as Guido Galletti's 'Holy Father' or the 'monument to Christopher Columbus', located in Piazza Acquaverde. The statues had to undergo expensive restoration work to reconstruct the missing pieces while local police patrols were put in place at the maritime station to check passengers' luggage.

Among the things most commonly left behind in the station waiting rooms are the little notes jotted on slips of paper. These are mostly address books made up of foreign numbers that allowed travellers to remember and call family members once they arrived at their destination, using the city's public telephones. One of the best known stories linked to these numbers is that of Rodrigo Noya and Clarissa Benei. It was 1976 and during one of his journeys, Rodrigo, a young Puerto Rican man, landed in Genoa where he stayed for a week.

During a popular party organised in the San Vincenzo district, Rodrigo met Clarissa, a Genoese literature and philosophy student. The two fell in love instantly and the combination of the heat of the moment and the difficulty in overcoming the language barrier led them both to develop their own language. When Rodrigo had to leave, Clarissa, through a dedication, tried to transcribe this hybrid language with signs. We do not know if the girl ever delivered the letter to her beloved or if the latter purposely left this writing at the station, but the notes were found by a ship's captain on one of the waiting chairs.

Audioguide text #7 - The Sauli Del Carretto Centurions

The latest story we are about to tell you involves one of the most mysterious and obscure families of the ancient republic of Genoa. Some of the palaces owned by the Centurion Sauli Del Carretto were on the lists of the 'Rolli', the list of residences that were coveted by high dignitaries in transit through Genoa on State visits. The palaces, catalogued according to the magnificence and prestige of their owners, were mostly grouped along the 'new' streets such as today's Via Garibaldi and were chosen to host the visiting personage according to his rank and a random draw. Travellers, actors, famous people were hosted during their cultural, economic or simply tourist Grand Tours.

The origin of the Centurion family is uncertain: according to a Locarnese chronicle of 1636, the progenitor, Umberto, fled France in the 10th century and settled in Cimalmotto; according to another hypothesis, he came from the Ossola valley. This little information is mostly due to the fact that the family, from its very beginnings, maintained an excessive secrecy that later led other noble descendants to arouse suspicion and assiduously observe the lineage's movements.

The Centurions' main passion was winter hunting in the Ligurian territory, along the Scoffera pass. In particular, Paolo, the son of Umberto Centurion and Barbara Sauli, instituted an annual fox and wild boar hunting competition in 1695, animals that were included in the family coat of arms in the 18th century. Outside the hunting season, the members of the competition used to meet inside the family palace in Via dei Giustiniani, later nicknamed 'Palazzo Caccialor'.

During the private meetings, the topics were so exclusive that the Centurions bound the guests who wished to attend to absolute secrecy, arousing even more suspicion in the family from the other noble dynasties.

Audioguide text #8 - A grotesque collection

Between 1885 and 1905, the Centurion Sauli Del Carretto family was hit by a severe financial crisis as a result of the building boom that was raging in Genoa, forcing them to auction off most of their property, including Palazzo Caccialor. In the later 1960s, clearance work began inside the building, which by then had become public, revealing a secret door behind one of the sideboards in the main dining room. The passage led into an underground room that housed a grotesque collection belonging to the family, a wunderkammer where organic remains and macabre artwork were meticulously preserved.

What the researchers have taken from the site and brought to the exhibition includes a selection of animal parts, unidentifiable shreds of skin, images of 'alien' anatomy, as well as paintings that seem to depict sects, shamanic and funeral rites that were discovered in the palace. Looking at these objects, it is intuitable to link them to the hunting world undertaken by the Centurions, but also to the actual activities of the hunter members who probably held their meetings in the dungeon. No writings or evidence have been found on what was undertaken during these macabre covens, nor whether they led to consequences or concealed even more ambiguous stories.